On May 15, 1756, Britain declared war on France, opening the

Seven Years War, the American part of which was called the French & Indian War. Though that was the official start of the French & Indian War, fighting had actually been going on for almost two years before that between the French and British in America. Beginning even earlier, however, was a cartographic war which was very much a prelude to the “hot” war that followed.

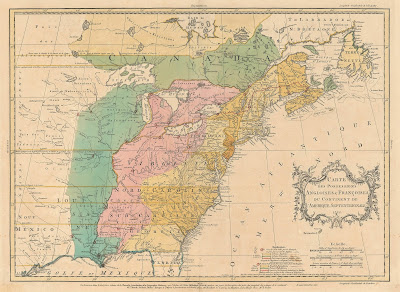

By the late seventeenth century, the French colonies in America consisted of two main parts.

New France, or

Canada, bordering the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, and

La Louisiane, considered by France to include the entire Mississippi River basin. The British lands in America at that time consisted of a series of colonies along the Atlantic coast, with a number of the original charters stating that they ran “from sea to sea,” though in practical terms they were limited to lands east of the Appalachian Mountains.

It wasn’t long before the British colonies began to look to expand. Their population was growing rapidly; for instance, it grew from about 250,000 in 1700 to over 1 million by 1750. The French were naturally concerned about British expansion. They had a relatively small population (only about 50,000 Europeans in 1750), and they saw British expansion as creating competition to their fur trapping and Indian trade.

This led to a series of Wars: King Williams War (1689-97), Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), and King George’s War (1744-1748). Despite all this fighting, the treaties which ended those wars did not resolve the problems between the French & British in North America.

The Treaty of Utrecht ended Queen Anne’s War in 1713. By its terms, the French ceded to the British the lands around Hudson’s Bay, the island of Newfoundland, and Acadia, which the British called Nova Scotia. The problem with the treaty, though, was that the exact definitions of the regions mentioned were ambiguous, with a boundary commission supposed to adjudicate the exact borders. The commission didn’t meet until 1720, and then never really got anywhere.

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended King George’s War in 1748. By that treaty, North America was supposed to return to the situation ante bellum. However, what that situation was, was no clearer then than it had been at the end of the previous war.

Naturally, French and British mapmakers tended to reflect their nation’s outlook on the issues related to North America, and this led to what has been called a “cartographic war.” This notion is well known among map dealers and collectors, the idea being that the maps for each side made claims promoting their colonies while diminishing the other country’s colonies. The idea is that each side was ‘flying the flag’; reflecting national pride. However, the cartographic war was much more than this and the story is worth examining closely.

Maps were one of the few ways European powers could establish their claims to territory. In the wilderness of North America, with relatively few settlements at the edges of the territories, the location of a border was often not marked in any way in the physical world. A line drawn on the map might be the only physical manifestation of a border. Sometimes, maps created the territories more so than any action on the ground.

Borders depicted on maps could have a reality beyond simply a line drawn on paper. Printed maps have an aura of legitimacy. If a feature is “on the map” the tendency is usually to accept it as real. If a particular border line was not questioned, then this could be taken as

de facto evidence of its acceptance. Also, treaties often referred back to previous political situations, and what was shown on maps was sometimes the only way that this could be determined.

Besides their reifying power concerning borders, maps also had a considerable influence on public opinion. For instance, they could stir up the public if citizens thought another country was taking away their land, stiffening their resolve to resist any diminishing of the territory as shown on a map. The public’s attitude could in turn influence the government, so maps did sometimes have an effect on government decisions.

For all these reasons, the cartographic war which raged in the first part of the eighteenth century is best seen as a non-military, but still significant part of the conflict between France and Great Britain.

The first map in the cartographic war was this one by British cartographer Herman Moll. It was issued just two years after the Treaty of Utrecht as a statement of the British view of her colonies as determined by that treaty.

In the north it shows the British colonies as extending all the way north to the St. Lawrence River and up to the Great Lakes as far as Lake Erie. The colony of Carolina, which has its own inset, is shown extending south to just a bit above St. Augustine.

This British volley was answered just three years later by French cartographer, Guillaume Delisle.

Delisle moved the British border well south and east of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. He also claimed that Carolina was named after Charles IX of France and settled originally by the French, in effect claiming that region for France as well.

This map provoked considerable consternation in Great Britain. Because Delisle was the Premier Géographe du Roi, that is geographer to the King, his maps were regarded as semi-official, reflecting the views of the French government.

The publication of Delisle’s map provoked Herman Moll to issue a new map of North America to highlight the “Incroachments” shown on Delisle’s map, as a warning to the British of what the French were doing. A note on the map explained that

“All within the Blew Colour of this map, shews what is Claim’d by France...According to a French Map published at Paris with the French King’s Privelege. The Yellow Colour what they allow ye English.” Moll concluded that “any body may see how much they [that is the French] would Incroach &c.”

The New York officials were particularly upset about the French cartographic claims, as much of the land they considered to fall within their jurisdiction was usurped in Delisle’s map. Governor William Burnet wrote to the Board of Trade that “I observe in the last Mapp published at Paris with Privilege du Roy par M. de Lisle in 1718...that they are making encroachments on the King[‘s] territories...”

Many of the British claims around the Great Lakes were based on their long standing relationship with the Iroquois, especially concerning the treaties which they believed gave them the rights to the Iroquois lands. This British position was reinforced by a clause in the Treaty of Utrecht which stated that the Iroquois were British subjects. In 1724, Cadwallader Colden, the Lieutenant Governor of the colony, issued the map above to show how the region around the Great Lakes belonged to New York through their treaties with the Five Nations.

The British government felt the need for better maps, so it ordered the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, more commonly called the Board of Trade, to send a circular letter on this point to the Governors of the various colonies. The Board was the primary policy-making and administrative agency for the British colonies and in 1719 it sent the following instructions:

“It being necessary for H.M. Service and for the benefit of the Plantations, that the limits or boundaries of the British Colonies on the Continent of America, should be distinctly known and marked out, more particularly so far as they may border on the settlements made by the French or any Foreign Nations, we desire you to send us, as soon as possibly can, the best informations [sic] you can get upon your Government, together with a chart or map, and the best accounts and vouchers you can obtain to support the same....”

David Rumsey Map Collection

This resulted in a number of new maps being sent to the Board from the colonies. As the maps arrived in London, an assistant clerk to the Board, Henry Popple, compiled a general map of the “British Empire in America” with the Board’s “approbation.” As he stated on the map

“great care has been taken by comparing all the maps, charts, and observations that could be found, especially the authentick records and actual surveys transmitted to their Lordships by ye governors of the British Plantations and others to correct ye many errors committed in former maps.”

Issued in 1733, Popple’s production was a huge and detailed map which represented the best British mapping of the continent to date. The Board of Trade initially seemed impressed, writing to the Lords of Treasury that

“Mr. Henry Popple having with great care and Diligence drawn a Map of the British Empire in America, which, from the assistance he has had, from the best Charts and actual Surveys, is rendered infinitely more complete than any other now extant.”

Not only was the map detailed and based on the “best Charts and actual Surveys,” but it exhibited an expanded view of British holdings in America compared to Delisle and Moll. Nova Scotia is depicted as extending north all the way to the St. Lawrence River, and New York and Pennsylvania are shown reaching to the Great Lakes, while North and South Carolina are clearly depicted as British colonies.

However, British critics soon appeared. Popple was criticized for relying too much on French maps for his sources and for not taking a strong enough position relative to the extent of the British colonies. For instance, though New York and Pennsylvania reach the Great Lakes, Fort Niagara, on the eastern side of the Niagara River, is shown as part of French Canada. In 1738, Cadwallader Colden, clearly referring to the Popple map, wrote that “The English maps are such servile copies of the French that they mark out the boundaries between the English and French with the same disadvantage to the English as the French do.”

In the 1720s and 30s, the main area of conflict between the French and British in North America concerned the region north of New England and south of the St. Lawrence River. By the Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, the French had ceded “all of Nova Scotia or Acadia, in its entirety, conformable to its ancient borders.” The British understood “Nova Scotia” as encompassing the entire region up to the St. Lawrence, today’s New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, whereas the French understood it as applying only to the Nova Scotia peninsula.

In 1740, political tensions in Europe led to the War of Austrian Succession, between Austria and France allied with Prussia. Great Britain was drawn into the war as an ally of Austria, declaring war on France in 1744. The war between France and Britain almost immediately led to armed conflict in the northern parts of America, what is called King George’s War. Various raids and battles occurred, with the only major event being the British capture of the fortified French port of Louisbourg. This war ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1747, which essentially restored the situation in North America ante bellum, a situation which, as I have said, was ambiguous and contentious.

Like with the Treaty of Utrecht, the new agreement called for an Anglo-French commission to meet and determine the borders of the regions referred to in the treaty. Beginning in 1750, commissioners met in Paris to negotiate on these matters. By that time, two main areas of conflict had developed. One was the old issue of what meant by “all of Nova Scotia or Acadia according to its ancient borders.” The other concerned the Ohio River Valley.

The French well knew that the British colonies were wealthier and more populous than their own, and they were afraid that the British would expand westward into the regions they depended on for their fur trapping and Indian trading. In 1749, Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville led a French expedition down the Ohio River, leaving engraved plates along the way expressing French claims for the Ohio River.

Meanwhile, the British were starting to focus on their own claims to the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, based on the original charters. A number of groups were formed to pursue British settlement and development across of the mountains, and these were granted large tracts of land by British colonial governments. Obviously, French and British interests conflicted in the Ohio River Valley.

Library of Congress

This map by British map publisher Robert Sayer shows, from the British perspective, “The Limits of His Majestys several Provinces...here laid as they at present exercise their Jurisdictions.”

The British colonies are shown encompassing all the lands south of the St. Lawrence, and extending all the way to the Mississippi. To make sure the point was clear, Sayer added a note that said:

“The French have streched [sic] their Louisiana on both sides the Mississipi [sic], which is another instance of their Incroachment, for they have no just claim to any part of the Country lying Eastward of that River.”

The French and British border commissioners, trying to determine what were the “ancient borders” referred to in the treaty, naturally looked at maps published previously as part of the negotiations. However, they could find no consistency nor clear answer, as the maps, both those made by the French and by the British, were unclear and showed contradictory information.

Library of Congress

The Acadian boundary dispute was the most important part of the negotiations for both the French and the British commissioners, for it was seen as the key to the sea routes to and from North America and the economic wealth from the nearby fisheries. Thus French and British mapmakers paid special attention to the details in the mapping of the region. One of the leading French mapmakers, Didier Robert du Vaugondy issued a map of Canada in 1753 which made no mention at all of “Nova Scotia” and showed Acadia as referring to a just a small strip along the bottom edge of the peninsula.

This map caused quite a stir in Great Britain, for not only was Vaugondy’s map dedicated to the French secretary of state, but he advertised that his map was based on reports communicated to him from the Ministry of War, implying it represented official French policy. As what the designation “Acadia” referred was just the point then being negotiated by the Boundary Commissioners, Vaugondy had to provide a retraction stating that his map did not reflect an official government position.

Library of Congress

Vaugondy’s map, naturally, provoked a British response with this map by Bradock Mead, which shows Nova Scotia as extending from the peninsula all the way to the St. Lawrence River. Mead was very clear in his attitude to the French maps that claimed otherwise, writing in a 1754 pamphlet, “[France’s] geographers and historians have been influenced to prostitute their pens in the most shameful manner, to serve the injurious cause.”

Interestingly, the Popple map, which had been made specifically to support the British position in North America, actually caused the British negotiators problems two decades later with their claims to the Ohio River Valley. The French commissioners pointed out that Popple did not show the British colonies extending beyond the Appalachians, and that since Popple stated on the map that he “undertook this Map with ye approbation” of the Board of Trade, this implied that it reflected the official British position at the time.

The British had to reply that while the Board “might very well [have approved] of such an Undertaking,” Popple’s map was

“framed according to his own particular Notions; he published it upon his own single Authority; the Board of Trade at the Time gave it no extraordinary Sanction... it has ever been thought in Great Britain to be a very incorrect Map, and has never in any Negociation between the two Crowns been appealed to by Great Britain as being correct, or a Map of any Authority.”

In any case, the Boundary Commission negotiations continued through 1753, but no progress was made and soon the commissioners were recalled. Negotiations didn’t stop, however, but changed their nature. The Boundary Commissioners had been tasked with determining what was meant by the terms of the existing treaties, but now there was direct negotiations between British and French officials to work on a new geopolitical agreement with newly determined borders. The discussions continued to focus on the Acadia question and the trans-Appalachian region, with various proposals being put forth, including the possibility of having a neutral ground in between the French and British colonies, with rights to free access by traders of both nations.

The Boundary Commissioners had used old maps to try to determine existing borders, but in the new negotiations, the British officials wanted accurate maps upon which to establish new boundaries. The problem was that with the discrediting of Popple’s map, they did not have any really good British-made maps of North America. Consequently, in 1749, the Earl of Halifax, the president of the Board of Trade, commissioned a prominent Virginia-born physician, John Mitchell, to compile a map of North America using the Board of Trade’s archives. Mitchell produced a manuscript draft in 1750, but this was seen to be inadequate. Thus the Board sent out another directive to the governors of the American colonies for them to have better maps made and sent to London. As the new maps came in to the Board from the colonies, Mitchell was given access to them.

Newberry Library

The result was that in February 1755, Mitchell’s huge “Map of the British and French Dominions in North America” was published. Mitchell not only used the latest information, but he based the political borders on the original Royal charters and patents, showing the colonies as extending well beyond the Appalachians, and indeed beyond the Mississippi to the edge of the map. In the northeast he showed British lands as not only reaching up to St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, but also to lands north of Lakes Ontario and Erie.

It is interesting to note that the Earl of Hardwicke, the British Lord Chancellor, who was in charge of the negotiations then going on with the French, was very concerned about the publication of the map. He wrote:

“I fear very inconvenient Consequences from it, for it carries the Limits of the British Colonies as far, or farther than any other, which I have seen. If it should out just at this juncture with...the Sanction of the Board of Trade, it may fill people’s heads with so strong an opinion of our strict Rights, as may tend to obstruct an Accommodation, if attainable, ...& make what may be necessary to be done to avoid the fatal Evil of a War, the Subject of great Clamour.”

This is actually just what the Board of Trade intended. The Earl of Halifax, the President of the Board, was a hawk in terms of British rights in North America and he specifically wanted the Mitchell map to be released so as to pressure His Majesty’s Government not to concede too much to the French.

That the Mitchell map had an impact on the British public is clear, for reduced versions of the map were published in at least four different British “gentleman’s magazines” within the year.

Illustrated monthly magazines first appeared in London in 1731. These magazines, with such names as Gentleman’s Magazine and London Magazine, contained poetry, prose, and articles on events, fashions, personalities, and other items of the day that might be of interest to the British gentleman. Illustrated by wood and copper engravings, the magazines included many maps, often related to current events.

Naturally, the tensions with the French generated a good number of maps, some appearing as early as the 1740s but then a large number by 1755, when at least 18 magazine maps related to the conflict in North America were issued.

These maps not only informed readers on the events taking place over the oceans, but they also helped to sway public opinion. The many copies of Mitchell’s map in the British magazines, and of course the extraordinary original eight-sheet Mitchell map itself, had a considerable effect on the British public, stiffening their attitude towards any sort of compromise with the French. Not surprisingly, the British government began to take a harder line and very soon the negotiations with the French were broken off.

Click here to see maps of the French & Indian War

While these negotiations had been going on—-to no avail-—events in North America were progressing on their own towards war. Fighting in western Pennsylvania, combined with increased public fervor concerning the French “Incroachments,” as well as concerns elsewhere in the British empire, led to the inevitable declaration of war on May 15, 1756.