New England is the home of some of the best institutional print collections in the country. I have already written about the Connecticut Historical Society and the American Antiquarian Society, and today I will talk about another New England institution with a world-class antiquarian print collection, the Boston Athenaeum.

For almost three decades, Sally Pierce was the Athenaeum's Curator of Prints & Photographs. Sally is a superb print scholar, author (and wonderful person), who helped to turn the print collection at the Athenaeum into one of the best in the country. From 1991, Sally was assisted by Catharina Slautterback, who also co-authored a number of publications with Sally. When Sally recently retired, it was natural that Catharina would succeed her as Curator of Prints & Photographs. The Athenaeum was very lucky to be able to pass on the baton to such a capable, knowledgeable and experienced successor. Catharina has graciously agreed to be interviewed in this blog about the Athenaeum and its collection.

What is the history of the Athenaeum’s collection?

The Boston Athenaeum was founded in 1807 as a library, art repository, natural history museum, and laboratory. In the 1820s, the Athenaeum opened an art gallery, one of the first public venues for exhibiting art in New England. Although paintings and sculpture were the focus of both the Athenaeum’s art collection and its exhibitions, works of art on paper were routinely acquired and displayed. Most of the prints were acquired through donations and ran the gamut from European portraits, landscapes and city views to locally produced engravings and lithographs. Although several important early American artists, such as David Claypoole Johnston, Benjamin Nutting, and Seth Cheney, were nominally in charge of the “Engraving Room,” there was no clear collecting policy or curatorship in the modern sense of the word. The collection grew accordingly with the exquisite and the mundane coexisting in less than ideal housing environments. In the 1870s, the majority of the Athenaeum’s art collections were put on long term loan with the newly formed Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Athenaeum focused on its mission as a library. Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, works of art on paper were purchased primarily, although not exclusively, for documentary purposes, i.e. as art or geographical references.

The Boston Athenaeum was founded in 1807 as a library, art repository, natural history museum, and laboratory. In the 1820s, the Athenaeum opened an art gallery, one of the first public venues for exhibiting art in New England. Although paintings and sculpture were the focus of both the Athenaeum’s art collection and its exhibitions, works of art on paper were routinely acquired and displayed. Most of the prints were acquired through donations and ran the gamut from European portraits, landscapes and city views to locally produced engravings and lithographs. Although several important early American artists, such as David Claypoole Johnston, Benjamin Nutting, and Seth Cheney, were nominally in charge of the “Engraving Room,” there was no clear collecting policy or curatorship in the modern sense of the word. The collection grew accordingly with the exquisite and the mundane coexisting in less than ideal housing environments. In the 1870s, the majority of the Athenaeum’s art collections were put on long term loan with the newly formed Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Athenaeum focused on its mission as a library. Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, works of art on paper were purchased primarily, although not exclusively, for documentary purposes, i.e. as art or geographical references.The haphazard growth of the Athenaeum’s prints and photographs collection, so typical of the times, changed dramatically in the mid-twentieth century. In 1943 Charles E. Mason, Jr. and others founded the New England Historical Art Society to promote the study of the “history and customs of New England as portrayed in paintings, prints, engravings, sculpture, and other works of art.” The Society was one of a number of organizations and individuals that sought to challenge existing prejudices against American art and specifically American prints. In 1949 the Society was dissolved and its collection donated to the Boston Athenaeum, thus forming the nucleus of an independent prints and photographs department within the institution.

The Athenaeum’s collection was thus transformed from a large, but loose, assortment of prints and photographs to a tightly focused collection documenting New England culture, history, and printmaking. In its early years, the Department benefited from the guidance and generosity of Charles E. Mason, Jr., known affectionately as “Monk,” and one of the earliest and most enthusiastic collectors of American prints, particularly Boston lithography. Sally Pierce became Curator in 1981 and under her stewardship, the Prints & Photographs Department expanded to become one of the nation’s most significant collections of early American works of art on paper. I joined the Athenaeum in 1991 and assumed the curatorship of the Department following Ms. Pierce’s retirement in 2009.

What is the range of prints in the Athenaeum graphics collection?

Today, the Athenaeum’s Prints & Photographs Department is an active and vibrant member of the American print world. The collection is consulted by researchers around the world and individual items are exhibited and reproduced on a regular basis. The collection is comprised of works of art on paper documenting New England and American history from the eighteenth century to the present. Although classified as a historical documentation collection, many of the Department’s objects also have great artistic and aesthetic merits.

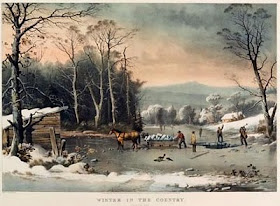

Today, the Athenaeum’s Prints & Photographs Department is an active and vibrant member of the American print world. The collection is consulted by researchers around the world and individual items are exhibited and reproduced on a regular basis. The collection is comprised of works of art on paper documenting New England and American history from the eighteenth century to the present. Although classified as a historical documentation collection, many of the Department’s objects also have great artistic and aesthetic merits.  Its holdings include the graphic work of artists as diverse as Paul Revere, John Carwitham, Abel Bowen, Winslow Homer, Fitz Henry Lane, and William Morris Hunt. All manner of printmaking is documented within the collection, from aquatints and etching, to mezzotints, lithographs, and the four-screen processes of the early twentieth century. The subject matter of the collection is equally diverse with portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, urban and factory views, as well as significant holdings in Civil War-related imagery. In addition to prints, the Prints & Photographs Department actively collects photography, drawings, watercolors, posters and architectural drawings. A fuller description of the Department’s holdings can be found on the Athenaeum’s website.

Its holdings include the graphic work of artists as diverse as Paul Revere, John Carwitham, Abel Bowen, Winslow Homer, Fitz Henry Lane, and William Morris Hunt. All manner of printmaking is documented within the collection, from aquatints and etching, to mezzotints, lithographs, and the four-screen processes of the early twentieth century. The subject matter of the collection is equally diverse with portraits, landscapes, genre scenes, urban and factory views, as well as significant holdings in Civil War-related imagery. In addition to prints, the Prints & Photographs Department actively collects photography, drawings, watercolors, posters and architectural drawings. A fuller description of the Department’s holdings can be found on the Athenaeum’s website.What do you see as the greatest strength of the Athenaeum graphics collection?

The greatest strength of the Athenaeum’s Prints & Photographs Departments is undoubtedly its collection of nineteenth century Boston and New England lithographs. Boston was a center for the lithographic arts from the 1820s to the 1880s and home to such important firms as Pendleton’s, J. H. Buford’s, and Louis Prang. These firms produced a wide range of material: letterheads, sheet music covers, advertisements, political cartoons, playbills, and “art” chromolithographs. The Boston Athenaeum collects all of these materials and, in the process, documents not only the history of printmaking in America, and specifically in New England, but also the cultural, political, and social milieu of the nineteenth century.

The greatest strength of the Athenaeum’s Prints & Photographs Departments is undoubtedly its collection of nineteenth century Boston and New England lithographs. Boston was a center for the lithographic arts from the 1820s to the 1880s and home to such important firms as Pendleton’s, J. H. Buford’s, and Louis Prang. These firms produced a wide range of material: letterheads, sheet music covers, advertisements, political cartoons, playbills, and “art” chromolithographs. The Boston Athenaeum collects all of these materials and, in the process, documents not only the history of printmaking in America, and specifically in New England, but also the cultural, political, and social milieu of the nineteenth century. What part of the graphics collection would you most like to strengthen?

I am always looking to strengthen the Athenaeum’s collection of eighteenth and early nineteenth century prints in order to supplement our understanding of American printmaking. And I am continually adding to the Athenaeum’s nineteenth century lithographic collection. I am particularly interested in the work of three Boston lithographers.

The short-lived firm of Tappan & Bradford (later L. H. Bradford & Company) produced some of the most beautiful examples of the lithographic arts with a fineness of draftsmanship and subtle tonal printing unparalleled at the time.

The short-lived firm of Tappan & Bradford (later L. H. Bradford & Company) produced some of the most beautiful examples of the lithographic arts with a fineness of draftsmanship and subtle tonal printing unparalleled at the time. The chromolithographic work of Charles H. Crosby & Company is little known today; his output has been overshadowed by the more prolific and financially successful firm of Louis Prang. Crosby was an appalling bad businessman (he went in and out of bankruptcy several times) but he employed highly skilled artists and his firm produced some of the most ambitious and creative chromolithographic advertisements of the day. His work is fairly scarce and I would love to be able to document the full range of his work.

The chromolithographic work of Charles H. Crosby & Company is little known today; his output has been overshadowed by the more prolific and financially successful firm of Louis Prang. Crosby was an appalling bad businessman (he went in and out of bankruptcy several times) but he employed highly skilled artists and his firm produced some of the most ambitious and creative chromolithographic advertisements of the day. His work is fairly scarce and I would love to be able to document the full range of his work.  One of my favorite lithographic artists of the nineteenth century is the great portraitist, Leopold Grozelier. Although he died at the young age of thirty-five, he was incredibly prolific. The Athenaeum has over 80 portraits by Grozelier but I would like to continue to add to our holdings; it would be particularly interesting to acquire examples of prints that he executed in France before immigrating to the United States in 1851.

One of my favorite lithographic artists of the nineteenth century is the great portraitist, Leopold Grozelier. Although he died at the young age of thirty-five, he was incredibly prolific. The Athenaeum has over 80 portraits by Grozelier but I would like to continue to add to our holdings; it would be particularly interesting to acquire examples of prints that he executed in France before immigrating to the United States in 1851.Is there any one print or type of print not in the collection that you would like to add?

Like most curators, my desiderata, or want, list is endless and I can think of several examples of prints and type of prints that I would like to add to the collection. For example, the Athenaeum has not traditionally collected color wood cut prints of the early twentieth century. There was a particularly vibrant community of wood cut artists in New England at this time and it would be wonderful to add some of their work to the Athenaeum’s collection.

In addition to adding new objects to the collection, curators must often “upgrade” their existing historical prints. This is not discussed very often but in fact many eighteenth and nineteenth century prints have had a long and hard life before they end up in a public repository. They have frequently been exposed to light, backed in wood, and stained by water or other liquids. Many have also suffered from the overzealous conservation treatment, often irreversible, that was typical of the mid-twentieth century. The Athenaeum is not unique in having some prints that are too fragile or worn to be handled or displayed. When an important print is in bad condition, I will seek to “upgrade” it by purchasing a better impression when and if it becomes available on the market.

What is the most important task as curator at the Athenaeum?

My first and foremost task as a curator is to make the Athenaeum’s collection of graphic art accessible to researchers. There are many steps involved in making a work of art accessible. Work must be acquired, accessioned, cataloged, properly housed, shared with researchers and classes, and, in an ideal world, published and exhibited. As the sole employee of the Athenaeum’s Prints & Photographs Department, I am responsible for all of these tasks, many of which are quite time consuming. These housekeeping chores may not be particularly glamorous, but an object that is un-cataloged or improperly housed is not accessible to anyone. As a curator, I am eager for the objects under my care to be used and enjoyed by the present generation as well as future generations. I like to think that for every print in my collection there is at least one researcher. To increase the likelihood that researchers will find their prints, catalog records for the Athenaeum’s graphic arts collection are available on our on-line catalog “Athena.”

What projects do you have underway or planned for the Athenaeum for the future?

I will be working on a series of exhibitions for the Athenaeum’s Norma Jean Calderwood Gallery. The exhibitions will take place over the course of the next decade and will feature highlights from the Prints & Photographs collections. One of the first exhibitions will be devoted to the development of the chromolithographic arts in Boston in the nineteenth century. There are also plans for exhibitions on the Department’s collection of architectural drawings and recent acquisitions of contemporary art.

What long-term goals do you have for the graphics collection at the Athenaeum?

In 2000, the Athenaeum received an endowment for the purchase of contemporary works of art on paper. Contemporary works are acquired for their documentation of New England in the 21st century and as a record of artistic activities in the region. In selecting contemporary works, I consider how they relate and speak to the historic prints in the collection. For example, I have been purchasing the work of a local artist who photographs the decaying structures of former New England factories. The Athenaeum also owns nineteenth century prints of many of these buildings and together these works record the evolving history of the area’s built environment. A contemporary print is contemporary for only a short period of time before becoming “historic.” By acquiring works by living artists today, I am able to build a historic collection for the future.

Who uses the graphics collection at the Athenaeum?

A wide variety of researchers make use of the Athenaeum’s graphics collections. Many of the researchers are academics with specialties in American studies and the visual arts. Architects and architectural historians also use the collection heavily as do textbook publishers and film documentarians.

A wide variety of researchers make use of the Athenaeum’s graphics collections. Many of the researchers are academics with specialties in American studies and the visual arts. Architects and architectural historians also use the collection heavily as do textbook publishers and film documentarians. What is the most common request you get related to the graphics collection at the Athenaeum?

There are two major categories of requests for images at the Athenaeum: 1) the built environment and 2) social history. New England has a long history of reusing and transforming its buildings and I assist many researchers in their attempts to visually document the past and present lives of various structures. Social historians have become increasingly adept at using the visual arts to understand the past. Although there are trends in academia, there has been a strong and continued interest in abolitionism, African-American history, and gender studies over the course of the past few decades.

What other print collections (institutional) with American prints do you think are particularly good?

There are so many excellent public repositories of American historical prints in the country. In my neighborhood alone, there are several superb collections: the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, Historic New England, and the American Antiquarian Society. Many of these institutions have good on-line catalogs to their collections and they are all, without exception, overseen by wonderful, hard-working, and dedicated curators.