I spend a lot of time in the summer driving or biking around the mountains of Colorado. Colorado is one of the most beautiful places in the world and I am constantly filled with awe looking at the scenes of the state. Early visitors to Colorado were often impressed by the view of the Rocky Mountains from the plains and a few early prints were made of that scene (cf. the view of Pike's Peak from John Frémont's 1842 expedition above), but these were quite scarce and other than some scenes from the Pacific Railroad Surveys in the 1850s, there were scant images of the state up to the end of that decade.

Things changed, of course, when the Pikes Peak Gold Rush brought thousands of miners, and those who made money off of the miners, to the front range. Now there was a significant population here, which both brought new interest in and opportunities for the marketing of images of Colorado.

The first artist to really take advantage of this opportunity was A.E. Mathews (1831-1874). Mathews was born in England, but came to the United States at an early age and ended up being raised in Ohio. He worked as a typesetter, itinerant bookseller, and school teacher, with a predilection for landscape sketching. During the Civil War, Mathews served in the Union Army with Ohio troops for three years, making topographical maps and views. He also produced a number of excellent first hand images of scenes of the Civil War for a number of Cincinnati print publishers.

After the war, Mathews moved to nascent city of Denver, the main entrepot of the Pikes Peak Gold Rush. Mathews arrived in Denver November 1865, when Colorado was in the process of becoming a thriving mining region. In less than a decade, Colorado had been transformed from a sparsely settled backwater to a dynamic economic powerhouse. In 1866, the towns, such as Denver, Central City and Black Hawk, were exciting communities, with a veneer of civilization only somewhat covering over the raw frontier hotchpotch of gambling dens, saloons, and brothels.

Mathews decided he could continue his artistic career by producing a series of prints of Colorado to be sold to the new citizens, and those back in the East who might be interested. This resulted in 1866 with his Pencil Sketches of Colorado. This was a portfolio of twenty-three prints (which were also sold separately) showing thirty-six scenes in Colorado. The prints were lithographed in New York by Julius Bien.

Mathews’ Pencil Sketches captures the gold rush era of Colorado, a transient and foundational moment in the history of the territory. Mathews had a keen eye and considerable skill—-likely aided by a camera lucida—-so his images are accurate, detailed and filled with a sense of the time and place that is remarkable. The variety of the views is comprehensive, showing scenes of mining and processing, the landscape, and town, especially Denver with the three street scenes of particular note.

One of the fun aspects of this series is that, in order to make more money than from just selling the prints, Mathews offered Denver business owners the opportunity, for a fee, to have their businesses named in the three street scenes of the city. It is interesting how many businesses did accept this offer, though the unnamed shops in the scenes also indicate that not all bought into this scheme.

I have always loved the way that antique prints capture a period of our history, letting us see our past through the eyes of those who were there then, and there are no better views of from the past of Colorado than those by Mathews.

Thursday, July 21, 2016

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

George Pocock and his inflatable globes

George Pocock was a remarkable man who I found out about becaume of a fabulous "inflatable globe." Pocock ran a boarding school, Pocock’s Academy, for “young gentlemen,” and besides his pedagogical career, Pocock was an evangelistic preacher, church organist, and ingenious inventor.

The inventions I will discuss below were a series of inflatable globes for students, but Pocock also invented a “thrashing machine” for punishing errant students, constructed with a rotating wheel with artificial hands to spank the offending schoolboy.

Friday, June 3, 2016

Donald Trump and Currier & Ives

I have been reading a fascinating article by Hazel Brandenburg about the rise in popularity of Currier & Ives prints during the 1920s (from the American Historical Print Collectors Society magazine Imprint, Spring 2012). A great deal of the popularity of Currier & Ives prints then had to do with the fact that the “1920s were...a time of transition characterized by profound and lasting cultural changes...” This left Americans of the period feeling “uncomfortable with the present and anxious about the future” so “Americans turned their eyes to the past—or at least to a particular vision of an American past that seemed more authentic, uncomplicated, and pure.”

Monday, May 16, 2016

Were we (are we?) really enlightened?

Nineteenth century Americans and Europeans loved to do comparisons of places, societies and people around the world. 19th century atlases often contained charts showing comparisons of the heights of mountains, lengths of rivers, and so forth. A comparison of cultures was also something which would appear from time to time.

Monday, May 2, 2016

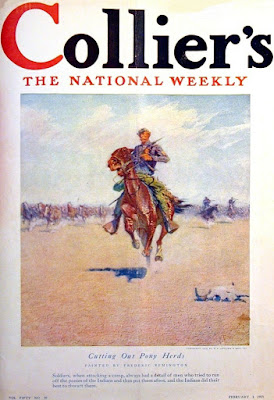

Western prints by Frederic Remington

To browse original prints by Frederic Remington - Visit us at PPS-West.com

Nowhere is the American West to be found more completely illustrated than in the works of Frederic Remington. Born an Easterner in upstate New York on October 1, 1861, he had by age 19, distinguished himself as a football player and pugilist at Yale. Leaving upon his father’s death, he arrived on the western plains in 1880 and found the demanding life to his liking, excelling in the use of the lariat and six-gun. He became friends with the working men of the times, prospected for gold, rode with military troops on campaigns, and roamed such fabled routes as the Santa Fe Trail and Bozeman Road. Remington quickly realized that he was witnessing the end of an era. As he wrote later in Collier’s Weekly: “I knew the wild riders and the vacant land were about to vanish forever-and the more I considered the subject, the bigger the ‘forever’ loomed.”

Five years later, with his inheritance exhausted and a net worth of three dollars, Remington arrived in New York City packing his voluminous portfolios resolved to break into art and illustration. Initial successes were thin, yet within 18 months editors were seeking him out and his painting, “The Courier’s Nap on the Trail” appeared at the annual exhibition in the National Academy. Within a few years he was recognized as the foremost western illustrator, short story author (Roosevelt preferred him to Owen Wister and Bret Harte) and sculptor of his day. Yet he continued to roam each summer for the increasingly elusive characters of the Old West. Fascinated with and befriended by the Indians, Remington anticipated the last rebellion by the Sioux. Narrowly escaping death in combat in the Badlands, he rushed to the East to document the events for Harper’s Weekly. Remington is unique for his “caught-in-action” style, a legacy of his lack in formal training and its stifling pedagogy--which he could never tolerate. He died in 1909 after surgery for appendicitis, his career at apogee, some 48 well-lived years of age.

There are essentially three types of original antique prints by Remington (there are lots of modern reproductions): magazine and newspaper illustrations, halftone prints sold separately or in portfolios, and original chromolithographs. These prints were all done for commercial purposes; that is, they were created with the intent to be used as illustrations in books or magazines, or for sale to the public to purchase to hang in their homes. They were issued in large numbers, though through attrition the antique Remington prints can be quite scarce.

Newspaper & Magazine Illustrations

The first commercial print after Remington was “Cow Boys of Arizona, Roused by a Scout,” issued in the February 25, 1882 issue of Harper’s Weekly (Remington had two illustrations published previously in college publications). The story is that Remington sent his sketch drawn on wrapping paper to the editors of Harper’s just to see if he could sell his work to the paper. They liked the image, but it was so crude that it had to be redrawn by staff artist W.A. Rogers.

In the next years, Remington sold a few more sketches to this illustrated newspaper, but he got his big break in 1886 when he was commissioned by Harper’s Weekly as an artist-correspondent to cover the U.S. government’s campaign against Geronimo. He never was able to catch up with Geronimo himself, so Remington focused more on “Soldiering in the Southwest,” taking many photographs and making sketches, which upon his return east he turned into illustrations for Harper’s and the magazine Outing. This was the beginning of a very successful career as an illustrator, with Remington providing art work for these and other publications, as well as providing images for books and art portfolios.

Between 1882 and 1913 Remington’s drawings and paintings appeared as original illustrations in seventeen publications. Initially, they were done as wood-engraving, but in the 1890s the publications started to use photomechanical screened halftones instead, so the later Remington illustrations tend to be made by this process. In the early twentieth century Collier’s Weekly and other publications started to reproduce his work as color halftones.

Portfolio Prints

Collier’s thought so highly of Remington’s work (one assume not only a commercial viewpoint, but also artistically), that in 1905 they began to issue color halftones after his paintings in portfolios and as separate prints. These were done in a number of sizes, over a number of years, and with different levels of quality. Interestingly, the early prints were called “Artists Proofs” by Collier’s. Traditionally, this term meant a print was pulled before publication, so the artist could inspect it, but Collier’s was simply using this terms as a selling tool. Collier’s also issued a number of Remington halftone images as separate prints for framing, again in different sizes.

Chromolithographs

The rarest and best quality prints by Remington are chromolithographs. These are images which were printed from multiple lithographic stones, one per color. The first of these were two prints, “Antelope Hunting” and “Goose Shooting,” issued in 1889 in a portfolio entitled Sport: or Shooting and Fishing. This portfolio included fifteen chromolithographs after important American sporting artists of the day, such as A.B. Frost, Frederic S. Cozzens, Frank H. Taylor and R.F. Zogbaum. For Remington to be included in this august group was evidence of his increasing fame.

Just over a decade later, in 1901, a portfolio was issued by R.H. Russell of New York containing eight lithographs based solely on Remington’s work. This set, A Bunch of Buckskins, included folio sized chromolithographs, four of ‘rough riders” and four of Native Americans.

A year later, Charles Scribner’s Sons reissued four prints, which had appeared previously in Scribner’s Magazine, as chromolithographs in a portfolio entitled Western Types.

The last chromolithograph after Remington was a separate print issued in 1908 of “The Last of His Race.” This print is an “oleograph,” which essentially is an elaborate chromolithograph printed using oil based inks on canvas and varnished so as to resemble an oil painting.

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

Thomas Nast Cartoons

Thomas Nast is one of our favorite artists. He is among the most famous illustrators of all time, often called the ‘father of American political cartooning.’ Nast was born in Bavaria in 1840 and at six years immigrated with his family to the United States. His father, a musician, had enrolled the artistically precocious child in an art school by age 12. Three years later Nast was forced to leave his training to help support the family, fortunately gaining work as an illustrator at Frank Leslie’s Weekly. Five years later Nast had traveled abroad to cover the Heenan-Sayers fight, later joining Garibaldi’s forces in Italy as a war correspondent. He had been employed by the New York Illustrated News for these assignments, but by early 1862 he had become a war correspondent again, this time for Harper’s Weekly. His patriotic themes created such attention that President Lincoln cited Nast as his “best recruiting sergeant”.

During the first 25 years following the War Between the States, Nast became the most significant illustrator of American political and social issues. His pointed cartoons exerted a great impact on public opinion. Every presidential candidate to gain his support won and his stature increased with the successful campaign in 1870-71 to bring down “Boss” Tweed of New York’s corrupt Tammany Hall and his political machine. More than a mere cartoonist, Nast was an innovator of images, popularizing or instituting many now familiar subjects such as the Republican elephant, the Democratic donkey, John Bull, Uncle Sam, and Columbia. Nast’s Santa Claus, modeled from Clement Moore’s St. Nicholas in his Twas the Night Before Christmas, serves as our present-day jolly old elf. Harper’s Weekly was Nast’s principal forum, and those prints hold a significant place in our American past.

On January 9, 1875, Nast produced a cover illustration for Harper’s Weekly applauding the proposed Specie Resumption Act which Grant had introduced to Congress and which passed just five days later. This had to do with the debate between “hard” and “soft” money proponents. In order the finance the Civil War, the federal government had begun to circulate paper money, “green backs,” which was not backed by gold specie. When the war ended, some wanted to continue with this policy, while others wanted to resume the use of a specie backed currency.

Most Democrats were soft-money advocates, hoping that inflation would be encouraged, so easing to some extent the extensive debt of their constituency, mostly farmers. Most Republicans, including Grant, were hard-money advocates, as were most of their capitalist supporters, and they believed that gold-backed currency would stabilized the money supply and sustained a prosperous economy. In the 1874 elections, the Democrats won enough seats that they were gong to take control of the House of Representatives, so the lame duck Republicans pushed through the Specie Resumption Act in early January, returning U.S. currency to a gold-based system.

Nast’s cartoon strongly backed this Act. Grant is shown standing on the “Ark of State, depicted as a Noah figure reaching out to the Dove of Peace, shown flying over a rainbow entitled “Our Credit.” Strewn behind the ark, floating in a sea of inflation, are the soft-money proponents.

Though the Act passed, the time-table for the retirement of the “green backs” was to take place over an extended period. The Democratic led Congress was not able to kill the act, but they were able to pass the Bland-Allison Act in February 1878, which succeeded in raising the amount of paper money not backed by gold allowed to be in circulation, thus diluting the Resumption Act.

The Republicans and Nast continued to be against this move, so Nast reissued his “Ark of State” cartoon, but this time reinforced his point by adding his own picture and titling the print with "Our Artist Indorsing the Above Cartoon.” Nast is shown sitting by the solid rock of “Sound Specie Basis,” with the quote “I, Th. Nast, A Fellow Workman Want 100 cents on a $ You Bet. Not 90 or 92 cents on a $ in silver, gold greenbacks of soft soap.”

This is all a rather obscure, and now the conflict seems totally out-of-date, but it is interesting to see Nast step into his own cartoons to reemphasize his position. He was a great innovator and print is a fascinating example of his work.

During the first 25 years following the War Between the States, Nast became the most significant illustrator of American political and social issues. His pointed cartoons exerted a great impact on public opinion. Every presidential candidate to gain his support won and his stature increased with the successful campaign in 1870-71 to bring down “Boss” Tweed of New York’s corrupt Tammany Hall and his political machine. More than a mere cartoonist, Nast was an innovator of images, popularizing or instituting many now familiar subjects such as the Republican elephant, the Democratic donkey, John Bull, Uncle Sam, and Columbia. Nast’s Santa Claus, modeled from Clement Moore’s St. Nicholas in his Twas the Night Before Christmas, serves as our present-day jolly old elf. Harper’s Weekly was Nast’s principal forum, and those prints hold a significant place in our American past.

On January 9, 1875, Nast produced a cover illustration for Harper’s Weekly applauding the proposed Specie Resumption Act which Grant had introduced to Congress and which passed just five days later. This had to do with the debate between “hard” and “soft” money proponents. In order the finance the Civil War, the federal government had begun to circulate paper money, “green backs,” which was not backed by gold specie. When the war ended, some wanted to continue with this policy, while others wanted to resume the use of a specie backed currency.

Most Democrats were soft-money advocates, hoping that inflation would be encouraged, so easing to some extent the extensive debt of their constituency, mostly farmers. Most Republicans, including Grant, were hard-money advocates, as were most of their capitalist supporters, and they believed that gold-backed currency would stabilized the money supply and sustained a prosperous economy. In the 1874 elections, the Democrats won enough seats that they were gong to take control of the House of Representatives, so the lame duck Republicans pushed through the Specie Resumption Act in early January, returning U.S. currency to a gold-based system.

Nast’s cartoon strongly backed this Act. Grant is shown standing on the “Ark of State, depicted as a Noah figure reaching out to the Dove of Peace, shown flying over a rainbow entitled “Our Credit.” Strewn behind the ark, floating in a sea of inflation, are the soft-money proponents.

Though the Act passed, the time-table for the retirement of the “green backs” was to take place over an extended period. The Democratic led Congress was not able to kill the act, but they were able to pass the Bland-Allison Act in February 1878, which succeeded in raising the amount of paper money not backed by gold allowed to be in circulation, thus diluting the Resumption Act.

The Republicans and Nast continued to be against this move, so Nast reissued his “Ark of State” cartoon, but this time reinforced his point by adding his own picture and titling the print with "Our Artist Indorsing the Above Cartoon.” Nast is shown sitting by the solid rock of “Sound Specie Basis,” with the quote “I, Th. Nast, A Fellow Workman Want 100 cents on a $ You Bet. Not 90 or 92 cents on a $ in silver, gold greenbacks of soft soap.”

This is all a rather obscure, and now the conflict seems totally out-of-date, but it is interesting to see Nast step into his own cartoons to reemphasize his position. He was a great innovator and print is a fascinating example of his work.

Friday, April 8, 2016

Terra Australis Incognita

I just returned from a wonderful trip to Australia, my visit "down under,” and so I am inspired to write about the mapping of the first “Australis,” Latin for ‘southern,’ to appear on maps, the mythical “Terra Australis Incognita,” that is ‘Unknown Southern Land.’

If you look on many maps of the sixteenth century, you will see a very large land mass covering the southern pole, looking much like the continent of Antarctica. This is really strange, as that continent was not actually discovered until 1820. If that is so, how did what looks to be Antarctica appear on maps from four centuries before? This anomaly has been explained by some (most famously Charles Hapgood in Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings) as being the result of an ancient advanced civilization or by others (such as Erich Von Daniken in Chariots of the Gods) as evidence of a visit to Earth by space visitors in the distant past. The truth, though more mundane, is still of considerable interest.

During the Renaissance, as scholars were trying to get a handle on their world in a period of discoveries of new lands, there were many who supported a theory that there had to be an as-yet-discovered continent in the southern-most part of the globe. This was based mostly on the supposition that there had to be a large land mass in the south to balance all the land in the north.

If you look at a modern map of the world [such as the one above by Daniel R. Strebe] and look all the land other than Antarctica, it is clear that the majority of the land mass is north of the equator. It was thought that if there were not a large, balancing land mass in the southern hemisphere, the globe would wobble or perhaps tip over.

Gerard Mercator was a proponent of this theory and so he included this continent on his world map.

Once one accepted that there must be a hitherto undiscovered land in the south, one tended to read any information about the southern regions as giving shape to this land. So Marco Polo’s report of “Greater Java” was seen as confirmation of this southern continent, and Polo’s “Locac” became the region of Lucach located there, as well as two other locations based on a misreading of Polo, “Beach” and “Maletur.”

The existence of this great southern land was then further confirmed when in 1520 Magellan sailed through the straits thereafter named after him. Magellan sailed between South America and what he called “Terra del Fuego,” which naturally was assumed to be the shore of Terra Australis. Thus it was that maps began to give a firmer shape to that continent.

However, Tierra del Fuego is an island, not part of Terra Australis, as was proven in 1616, when Jacques Le Maire and Willem Corneliszoon Schouten sailed from the Atlantic Ocean, south of Tierra del Fuego, and into the Pacific.

This did not get rid of the notion of Terra Australis Incognito, however, it just necessitated a modification of the shape of that putative continent. Map makers, not wanting to have to re-engrave entire new plates for their maps which had hitherto shown the continent including the northern shore of Tierra Del Fuego, simply erased the shoreline connected to the now-known-to-be island, ending the coast vaguely somewhere in the oceans to the east and west.

Through much of the seventeenth century, as explorations were being made in the southern oceans, new discoveries of land were often initially assumed to be part of Terra Australis-—for instance this was thought at one time for the New Hebrides and Australia—-until this was shown to be incorrect. As these discoveries were reported, parts of the coastline of Terra Australis, which had appeared on maps since the sixteenth century, were more and more erased, so that by the end of the seventeenth century, people were beginning to doubt its existence.

It was one of the greatest scientific cartographers of all time, Guillaume Delisle, who finally decided—-given the total lack of any evidence—-that he would completely remove the continent from his maps. Quite ironic that the person who was most closely following good, scientific principals in mapmaking, ended up making maps which were the furthest from reality.

The hope for a great southern continent continued into the eighteenth century, with James Cook having secret instructions to search for it during his 1768-71 voyage supposedly just to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun from Tahiti. On his second voyage, of 1772-73, Cook sailed around the seas so far to the south that he proved that if there were any southern continent, it was much smaller than the original theories suggested. It wasn’t until 1820 that the continent was first actually sighted, with the last of the known continents finally making it onto maps of the world legitimately, rather than as a matter of speculation.

Go to video about this cartographic myth

If you look on many maps of the sixteenth century, you will see a very large land mass covering the southern pole, looking much like the continent of Antarctica. This is really strange, as that continent was not actually discovered until 1820. If that is so, how did what looks to be Antarctica appear on maps from four centuries before? This anomaly has been explained by some (most famously Charles Hapgood in Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings) as being the result of an ancient advanced civilization or by others (such as Erich Von Daniken in Chariots of the Gods) as evidence of a visit to Earth by space visitors in the distant past. The truth, though more mundane, is still of considerable interest.

During the Renaissance, as scholars were trying to get a handle on their world in a period of discoveries of new lands, there were many who supported a theory that there had to be an as-yet-discovered continent in the southern-most part of the globe. This was based mostly on the supposition that there had to be a large land mass in the south to balance all the land in the north.

If you look at a modern map of the world [such as the one above by Daniel R. Strebe] and look all the land other than Antarctica, it is clear that the majority of the land mass is north of the equator. It was thought that if there were not a large, balancing land mass in the southern hemisphere, the globe would wobble or perhaps tip over.

Gerard Mercator was a proponent of this theory and so he included this continent on his world map.

Once one accepted that there must be a hitherto undiscovered land in the south, one tended to read any information about the southern regions as giving shape to this land. So Marco Polo’s report of “Greater Java” was seen as confirmation of this southern continent, and Polo’s “Locac” became the region of Lucach located there, as well as two other locations based on a misreading of Polo, “Beach” and “Maletur.”

The existence of this great southern land was then further confirmed when in 1520 Magellan sailed through the straits thereafter named after him. Magellan sailed between South America and what he called “Terra del Fuego,” which naturally was assumed to be the shore of Terra Australis. Thus it was that maps began to give a firmer shape to that continent.

However, Tierra del Fuego is an island, not part of Terra Australis, as was proven in 1616, when Jacques Le Maire and Willem Corneliszoon Schouten sailed from the Atlantic Ocean, south of Tierra del Fuego, and into the Pacific.

This did not get rid of the notion of Terra Australis Incognito, however, it just necessitated a modification of the shape of that putative continent. Map makers, not wanting to have to re-engrave entire new plates for their maps which had hitherto shown the continent including the northern shore of Tierra Del Fuego, simply erased the shoreline connected to the now-known-to-be island, ending the coast vaguely somewhere in the oceans to the east and west.

Through much of the seventeenth century, as explorations were being made in the southern oceans, new discoveries of land were often initially assumed to be part of Terra Australis-—for instance this was thought at one time for the New Hebrides and Australia—-until this was shown to be incorrect. As these discoveries were reported, parts of the coastline of Terra Australis, which had appeared on maps since the sixteenth century, were more and more erased, so that by the end of the seventeenth century, people were beginning to doubt its existence.

It was one of the greatest scientific cartographers of all time, Guillaume Delisle, who finally decided—-given the total lack of any evidence—-that he would completely remove the continent from his maps. Quite ironic that the person who was most closely following good, scientific principals in mapmaking, ended up making maps which were the furthest from reality.

The hope for a great southern continent continued into the eighteenth century, with James Cook having secret instructions to search for it during his 1768-71 voyage supposedly just to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun from Tahiti. On his second voyage, of 1772-73, Cook sailed around the seas so far to the south that he proved that if there were any southern continent, it was much smaller than the original theories suggested. It wasn’t until 1820 that the continent was first actually sighted, with the last of the known continents finally making it onto maps of the world legitimately, rather than as a matter of speculation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)