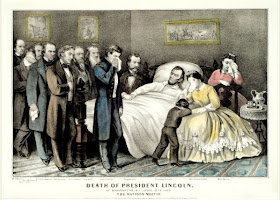

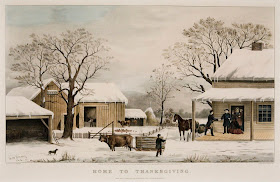

One of the most common ways to spot a Currier & Ives reproduction is that the size is wrong. While there are some reproductions that are made to the same size as the originals, by far most Currier & Ives copies are the wrong size. This is an important point, but it also brings up the general topic of sizes as related to Currier & Ives, the subject of this posting.

The first thing to know about Currier & Ives sizes is that they are usually, and should always be given for just the images themselves, not including the margins nor the title area, and the vertical size is given first. The primary reason for this is that the “standard” reference listing Currier & Ives prints, Frederic A. Conningham’s

Currier & Ives Prints. An Illustrated Check List gives the sizes in this way. Ever since it was first issued in 1949, this work lists the sizes of Currier & Ives prints (where they are given-—not all prints have their size indicated) “exclusive of margins.”

As Conningham's book became the standard reference for collectors and dealers from its first issue, and to some extent remains so today, it makes sense that those who work with Currier & Ives prints have followed Conningham in the way he gives measurements.

There are other reasons to do this as well. Gale Research’s listing of the prints (

Currier & Ives. A Catalogue Raisonne) does not follow Conningham, but gives the vertical size as including the text below the image. This problematic, not only because it creates a discrepancy between the two reference books, but more importantly because the text below the image is sometimes trimmed, especially where there is a small copyright line below the title. This makes it impossible to check the size compared to the listing. This is as opposed to Conningham's measurements, for the image is much less often trimmed. And, of course, as the margins of many prints are trimmed at least somewhat, giving the measurements of the full sheet of paper would be practically useless.

Interestingly, however, in one way the Conningham measurements are not usually followed today, viz. in the measurement of the prints in sixteenths of inches. It makes sense to measure in inches, for these are quintessential American prints and so an American measurement should be used. However, many dealers and collectors measure only to the nearest eight of an inch. First off, Conningham used the notation, e.g., 8.4 to indicate 8 4/16th, rather than the more standard 8 1/4, but beyond this there is an even more fundamental reason not to use sixteenths of an inch.

That is that the sizes of original prints actually vary by a fair bit. There are a number of reasons for this. One would be what paper was used and how it was prepared for printing, as different lots of paper would respond differently over time. Then the most common is that paper expands or contracts over time, depending on how it was treated, whether it got wet, was stored in a humid environment and so forth. Thus the image drawn on the stone might be 8 1/4 tall, but the image on the paper today can vary from this either by being smaller or larger, the former being more common.

There is also the fact that Currier & Ives are known to have used different stones to make the same print. In order to be able to run off a lot of the prints, they would sometimes have two or more stones of the same image going at the same time. In some of these cases there are noticeable differences in the images, but in others the images were essentially the same. These duplicate stones were made using a transfer process and in doing this, the size of the image on the stones could vary somewhat.

So to be as precise as 1/16th of an inch doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense. Whenever one measures a Currier & Ives print, one should allow some variation in the size. How much is hard to say. Certainly an inch is too much, but for a large folio prints I would think upwards of about 3/8th inch difference from the “recorded” size would be acceptable if all other indications are that the print is an original. (Generally there will be more variation on the longer side than the shorter side).

As I indicated above, Conningham does not give the exact size of many of the prints. He does, however, always give a size category: “V.S.” for “very small,” “S” for small, “M” for medium, and “L” for large. Thus it is that dealers and collectors almost always will categorize Currier & Ives prints as being either “very small folio,” “small folio,” “medium folio,” and “large folio.”

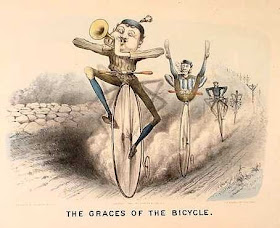

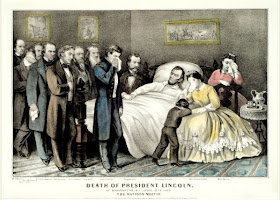

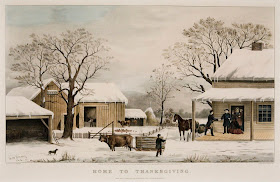

Interestingly, the Currier & Ives firm itself never used these designations. I am not sure who first used these categories, but Conningham admits that he gives them “for convenience.” It is certainly true that most Currier & Ives prints were done either in a “small folio” size of about 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 or in a very large size, bigger than about 14 by 20, but really it is simply a convention to put all the prints into these four categories. There is quite a difference in the sizes within each group, and this sometimes leads to differences of opinion over, for instance, whether a print is a largish small folio or a smallish medium folio.

For what it is worth, Conningham says that a very small folio print is up to 7 x 9, a small folio is approximately 8 1/2 x 12 1/2, a medium is between about 9 x 14 to 14 x 20, and a large folio is over 14 x 20. One oddity is that Gale Research’s listing accepts these measurements from Conningham, even though their measuring system it totally different! As they are using the text in the size, they should either have increased the vertical sizes of their categories or have said that their size categories used only the image size. However, as I indicated, I think Gale Research got the whole measuring thing wrong from the beginning.

What my shop does is give both the category size and the size of the image itself. We have also followed this measuring system for other prints and maps, though there is less universal acceptance of this for other types of prints. Still, for

Currier & Ives it is best to know and follow these conventions. It will help if you want to describe your print to someone else, it is the standard convention followed by most dealers who regularly deal with the prints, and it is the easiest way to check if you have an original or not.

For more on Currier & Ives, feel free to visit us at the

Philadelphia Print Shop West.

Sally was recently interviewed for the AHPCS's News Letter about some of issues involved with online exhibitions. Excerpts from this interview follows (note that if you join the AHPCS, you would get both the newsletter and journal with your membership...):

Sally was recently interviewed for the AHPCS's News Letter about some of issues involved with online exhibitions. Excerpts from this interview follows (note that if you join the AHPCS, you would get both the newsletter and journal with your membership...):